State of the (Diaspora) Arts

What do we know about immigrant and diaspora artists in the U.S?

We know that there are many of them, and their numbers are growing. In 2019, there were more than 400,000 immigrants working in creative or artistic occupations (New American Economy, 2019).

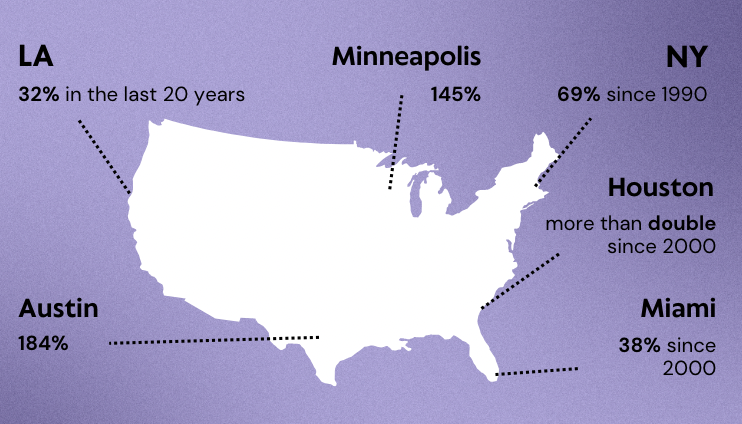

In major cities in the U.S, the number of immigrant artists have grown by 69% in New York (and not just because of the general increase in the population, as this was compared to a 30% increase in US-born artists); 32% in the last two decades in Los Angeles; a whopping 145% and 184% in Houston and Austin respectively; by more than double in Houston; and 38% in Miami since 2000 (Center for an Urban Future, 2020: 6).

We also know that artists from international backgrounds are celebrated for the diversity they bring. The above-mentioned report from Center for an Urban Future does not fail to mention that the Whitney Biennial in 2019 had 24 out of 78 artists hailing from outside the U.S, including Korakrit Arunanondchai (Thailand), Olga Balema (Ukraine), and Brendan Fernandes (Kenya). NEW INC, New Museum’s incubator for artists working in the conjunction of art, science, and technology, features more than 40% international artists in their cohort.

Brendan Fernandes, Night Shift in Romancing the Anthropocene, Nuit Blanche Toronto 2013 (Curators: Ivan Jurakic and Crystal Mowry). Courtesy of The City of Toronto, shared under Creative Common License (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

But let’s pause for a second and consider that out of the 400,000 immigrant artists, those who are just starting to promote their work in the U.S are not the ones being featured at the Whitney Biennial (or any other biennial).

Neither are aspiring creative workers graduating with a BFA immediately landing positions at major museums.

In fact, diaspora or not, contemporary art has one of the highest unemployment, career dissatisfaction, and wage gap. Out of 2 million arts graduates nationally, only 10 percent, or 200,000 people, make their primary earnings as working artists (BFAMFAPhD, 2014). In fact, fine arts majors ranked highest at 9.1% and also earned the lowest salary. Art History, History, and Sociology, the other top three majors leading to curator, archivist, and museum technician positions, followed with unemployment rates of 8%, 7.5%, and 5.5% respectively (Jimenez 2014). Even if you land a position, 68% of art museum workers have considered leaving the field, 74% cannot always cover basic living expenses, and it takes an average of 12 years before a worker receives a promotion (Los Angeles Times, 2023).

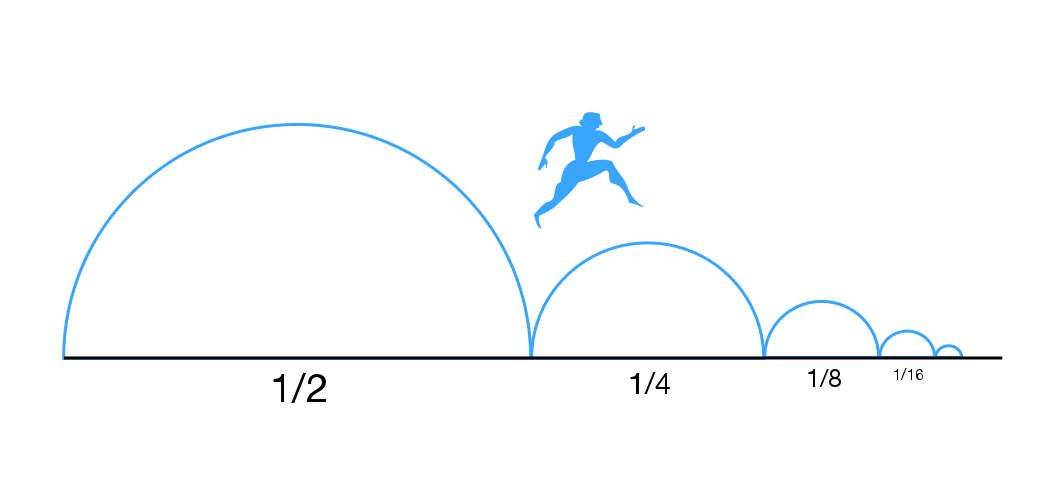

So how are immigrant artists going from Point A (deciding to pursue art professionally) to Point B (recognition, funding, publications on their work or, dare we say, “success”)?

Zeno’s Paradox. Grandjean, Martin (2014), shared under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Like Zeno’s arrow hurdling through infinite mid-points on its way from point A to B, consider these hurdles for each step of one’s creative career: If you are an artist living outside the U.S, you first need to enter the U.S either by enrolling in an institution or by gaining an exhibition or residency opportunity major enough to support their visa. Even if you resided in the U.S, you are most likely starting out by working on art part-time in addition to another (even several) job(s).

Artists are more than three times as likely as the U.S. workforce to be self-employed (34 percent versus 10 percent) - National Endowment for the Arts (2019)

Out of 2 million arts graduates nationally, only 10 percent, or 200,000 people, make their primary earnings as working artists. - BFAMFAPhD (2014)

You might then try to connect with a gallery dedicated to representing you. Other than independent galleries that invite open calls, commercial galleries do not have an open process for adding artists to their limited roster.

Only 29% of working artists are or had been represented by galleries. - Creative Independent (2018)

Even gallery representation does not guarantee a stable source of income:

Only 12 percent of survey participants count gallery sales among their top three sources of income. (Perhaps unsurprisingly, 29 percent also rely in part on family support or inheritance.) Nearly half of artists surveyed attribute less than 10 percent of their income to their art practice. - Creative Independent (2018)

Instead of relying on gallery and institutional representation, artists seek out support from nonprofit organizations or the government, in the form of fellowships and grants. However, these highly competitive opportunities require strategic selection of application material and intensive writing, skill sets more often acquired through trial-and-error and help from personal networks rather than formal education. In addition, many opportunities restrict their eligibility to U.S citizens or do not explicitly mark eligibility requirements.

“A good number of immigrant creators and artists emphasize the importance of networking, a finding that is also observed among non-immigrants creators (Tremblay, 2003; Tremblay & Pilati, 2008a, 2008b), but immigrant artists and creators appear to have more difficulty in accessing these networks, except those with an ethno-cultural link to a specific association…, government programs can be a support for integration into the labor market. However, for immigrant artists and creatives, not knowing which organizations could provide support can slow integration into employment.” - Journal of Workplace Rights (2016)

“From [those] 115 funding opportunities available to individual artists nationwide, only 33% explicitly state immigrant artists of various statuses can apply.” - Define American (2023)

Challenges facing diaspora artists illuminate structural issues in the art industry.

The exclusionary effect of jargon (or “art speak”) and academicism

is exacerbated for people who speak ESL (English as Second Language);

The lack of practical training and standardized resources towards creative careers is exacerbated for people who are new to the U.S or one of its regions;

Reliance on networking and collaboration is exacerbated for people who do not have established communities in the U.S with existing connections to contemporary art.

Diversity, Equity, And Inclusion (DEAI) missions at art organizations include various axes of diversity at the same time, including gender, sexuality, nationality, race, and disabilities. To translate these missions into actionable policy - which the American Alliance of Museums (AAM) urges U.S-based institutions do so by year 2025 - the different lived experiences of these diverse populations must be listened to and systematically addressed. Considering that globalization, diasporas, and displacement have been widely discussed in contemporary art in the last decade and more, the lack of studies addressing this population collectively - not just as artists as individuals - comes as a surprise.

Of course, part of this fuzziness originates from the ambiguity of the term “diaspora” itself. The African Diaspora and various Latine Diasporas may both use the term “diaspora,” yet are associated with different histories, motivations, and manners in which people moved (or were moved) from other regions of the world into the U.S. Simultaneously, personal experience of such a global movement is by no means a requirement for identifying a person of a diaspora. An artist could be born from parents who have immigrated, or may be inspired a deeper history from generations prior. One should rightfully resist generalizing these variations.

However, it remains that diasporas are lived realities for creative workers. They involve significant career challenges that are not only results of bias and discrimination but entangled with existing problems in the art industry at the level of how institutions operate, funds are disseminated, and research is conducted.

In particular, we see the fragility of our current system in the way COVID-19 disproportionately impacted immigrant communities.

Arab/Middle Eastern women reported the most percentage lost (70 percent of their income)... 55 percent of respondents reported having no savings. This percentage is higher in BIPOC respondents (66 percent) compared to white respondents (48 percent), with the most difference seen in Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (76 percent), Indigenous (73 percent), and Black respondents (72 percent). - Americans for the Arts (2021)

Flushing Town Hall, a multidisciplinary global arts venue in Queens, has lost more than $400,000 in earned income through June—over 17 percent of its annual budget—and projects losses up to $500,000 for the late summer and fall… The Nuyorican Poets Cafe has been closed since March with zero earned revenue and projected losses of between $400,000 and $450,000 for the year—more than half of its annual budget. The Bronx Academy of Art and Dance has lost over $20,000 in revenue from canceled events and rentals since March, and has spent more than $40,000 on continued rent payments for its shuttered space. - Center for an Urban Future (2020)

Much Ado about Flushing – The Municipal Art Society of New York. Courtesy of Street Lab, shared under the Creative Commons License

Through diasporas, we should realize once more that diversity is not merely an issue of “more different kinds of” identity but accounting for experiences of transnational movement and cultural adjustment.

Which is why, among countless disprivileged populations who deserve dedicated support in the arts, it is important to ask the specific question: How can global diasporas demand that the art industry do better?

Bibliography | Reading List

American Alliance of Museums, “Excellence in DEAI.” https://www.aam-us.org/2022/08/02/excellence-in-deai-report/

BFAMFAPhD. “Artists Report Back: A National Study on the Lives ofArts Graduates and Working Artists.” 2014. https://www.dropbox.com/s/3hai7psdenrbqec/BFAMFAPhD_ArtistsReportBack2014.pdf?e=1

Creative Independent. A study of the financial state of visual artists today. 2018. https://thecreativeindependent.com/artist-survey/

“Creativity is Boundless: An Inclusive Guide.” Define American, April 2023. https://defineamerican.com/research/creativity-is-boundless-an-inclusive-guide/

Fitzsimmons, Issac. “The Financial Impact of COVID-19 on Intentionally Marginalized Artists and Creative Workers.” Americans for the Arts, February 2021. https://blog.americansforthearts.org/2021/02/09/the-financial-impact-of-covid-19-on-intentionally-marginalized-artists-and-creative-workers

Jimenez, Darcy. “US College Majors With The Highest Unemployment Rates, Ranked.” Digg, 2024. https://digg.com/data-viz/link/majors-highest-unemployment-college-subjects-ranked

The Changing Face of Creativity in New York: Sustaining NYC’s Immigrant Arts Ecosystem Through Crisis and Beyond. Center for an Urban Future, December 2020. https://nycfuture.org/pdf/CUF_Changing_Face_of_Creativity_12-11.pdf

Tremblay, Diane-Gabrielle; Dehesa, Ana Dalia Huesca. “Being a Creative and an Immigrant in Montreal: What Support for the Development of a Creative Career?.” Journal of Workplace Rights (July-September 2016): 1-15. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/2158244016664237#:~:text=We%20found%20that%20these%20immigrant,difficulties%20in%20finding%20a%20job.

Rule, Alix; Levine, David. “international art english.” Triple Canopy. https://canopycanopycanopy.com/contents/international_art_english.