Moving Mountains, Crossing Seas: Motherhood in Korean Diasporas

For Mother’s Day, we explore four Korean artists who were inspired by the changing shapes of motherhood across two generations and different diasporic histories. Some of them were mothers themselves who paved new roles for women in society, while others contemplate their connection to their mothers and the mothers before, and through them, to history itself.

Modern Korean history was marked by conflict and loss, from the Japanese Occupation (1910-1945) and the division of the country into North and South soon after the end of World War II, to the Korean War (1950) and increasing number of families who moved abroad for better careers and education since the 1980s and 1990s. Each of these events came with movements of Korean people abroad for a better life - and for women, choosing such a path also meant choosing how to define motherhood on their own terms.

Seundja Rhee

Seundja Rhee (1918-2009) was one of the first generation of Korean women artists to pursue their careers in the French art scene. Yet, what she had to leave behind in Korea was as important to her paintings and printmaking as the influences she absorbed in Paris.

Seundja Rhee was a wife and mother before an artist. After graduating high school in Jinju, Korea and studying abroad in Japan, Rhee married a doctor with whom she had three children and led a comfortable life as a housewife. Just at the beginning of the Korean War (1950), however, continuing tensions between Yun and her husband would come to a head. Her husband and his family took sole custody of Yun’s three sons, leaving her to flee the war to Busan alone.

“The joy and happiness, the tragedies were buried in the depth of the ocean. I have arrived in Paris in peace. I have nothing with me. I do not know even a word of French. I have nothing. I am nobody. I am going to be reborn, reborn in foreign soil.” (MMCA, 2018)

From left: Rhee Seundja at Salon des Indépendants, 1956. At artist atelier in Ranelagh street, 1963. Courtesy of Gallery Hyundai.

While the feeling of loss must have been tremendous, it also appears to have motivated Rhee’s bold relocation to Paris, France in 1951 where she would launch her artist career with astounding success. “With each stroke, I imagined putting a spoonful of rice in my children’s mouths, and stroking their little heads,” she recalled. At the same time, she also reminisced on her own mother and family life from her childhood.

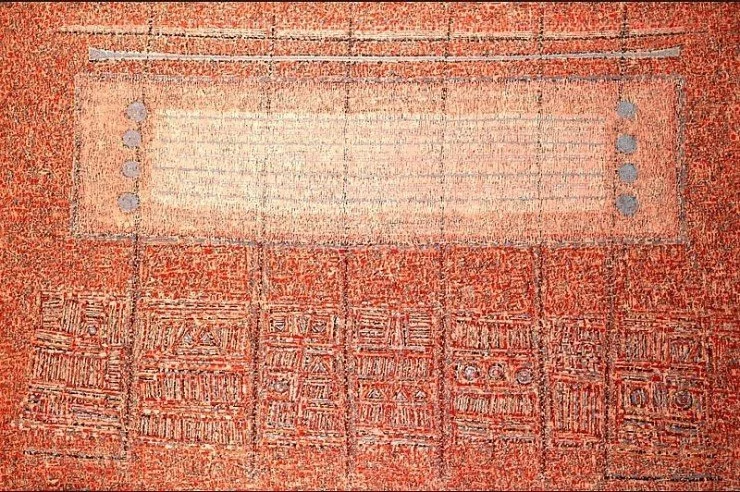

In the mixture of her nostalgia for her sons, her mother, and her home country at large, the figure of “mother as earth” became an essential feature in her unique adaptation of abstract painting. Rhee Seundja’s creative phase from 1961-1968 is entitled the “Woman and Earth” period. Despite physically being seas apart from her family, she assumes the role of mother as she redefined it: as someone that, like Earth, “covers fireballs of high temperature with its soil, accepting quietly storms and raging billows, while giving life to all things.” (Solo exhibition at Galerie Cavalero, Cannes, 1960; cited in Seundja Rhee Foundation) Indeed, she works the canvas in rough, raked layers of paint rather than clean, abstract forms, bringing to the forefront the painstaking and time-consuming labor that is often compared by critics to the gendered work of weaving or sewing.

“I am a woman, a woman is a mother, and a mother is earth.” (MMCA, 2018)

Seundja Rhee, A Mother I Remember, 1962, Oil on canvas, 130x195cm, Private Collection. Courtesy of MMCA.

Late when she returned to Korea after sixteen years, her four sons ended up becoming her most loyal supporters. Her eldest son was a college student at the time and the editor-in-chief of the college newspaper. He is said to have made a personal visit to the dean to request the Faculty Hall be used as the venue for Yun’s first exhibition upon return, as spaces fitting for large-scale paintings were rare in Seoul at the time. And when Rhee returned to Paris, he would accompany her as a senior reporter for major Korean press, Chosun-ilbo, and contributed to traveling exhibitions of masterworks from French museums to Korea. Following suite, Rhee’s second and third sons also moved to Paris and advocated for their mother throughout their lifetimes. After more than a decade apart, Seundja Rhee finally met a happy ending both as an artist and as an artist.

Yun Suknam

Yun Suknam was born in Manchuria in 1939, when Korea was still under Japanese Occupation. Then, she returned to Korea at the age of six. But it was only in the 1980s, as a mother well over the age of forty, that she started to pursue art.

“It just happened… When I was thirty-five or thirty-six, it suddenly dawned upon me that I could not keep on living just as a wife and homemaker.” (옆짚에 사는 예술가, 2017 - translated from Korean)

She started receiving lessons in calligraphy and oil painting, but eventually felt the instructors to be strict and limiting. Afterwards, Yun turned one of her spare rooms at home into a studio and decided to start being an artist on her own. So opened her very first solo exhibition in 1982, which depicted everyday scenes of Korean mothers at the marketplace. And in 1983, she had the opportunity to study at Pratt Institute and Art Student League in New York.

In the 1980s, Yun Suknam was active in the Korean women artists’ scene that tried to find its footing between the opposing camps of abstract modernist groups and the politically engaged Minjung Art movement. With interest in feminism starting in Korea in the late 1970s, Yun became one of the first artists to form artist groups such as Women’s Cultural Art Club focusing on women’s issues and to conduct research with intellectuals. While these women artist groups experienced to coalesce and dissipate due to each artist’s differing alignment with the dominant art movements of the time, they initiated a new perspective on motherhood that departed from the transcendental, all-embracing image of a mother. Instead, along with fellow artists like Park Youngsook, Yun Suknam became recognized as the “godmother of Korean Feminist Art” for focusing sharply on the lived reality of women, many of whom worked in factories or whose long hours of domestic labor went unrecognized.

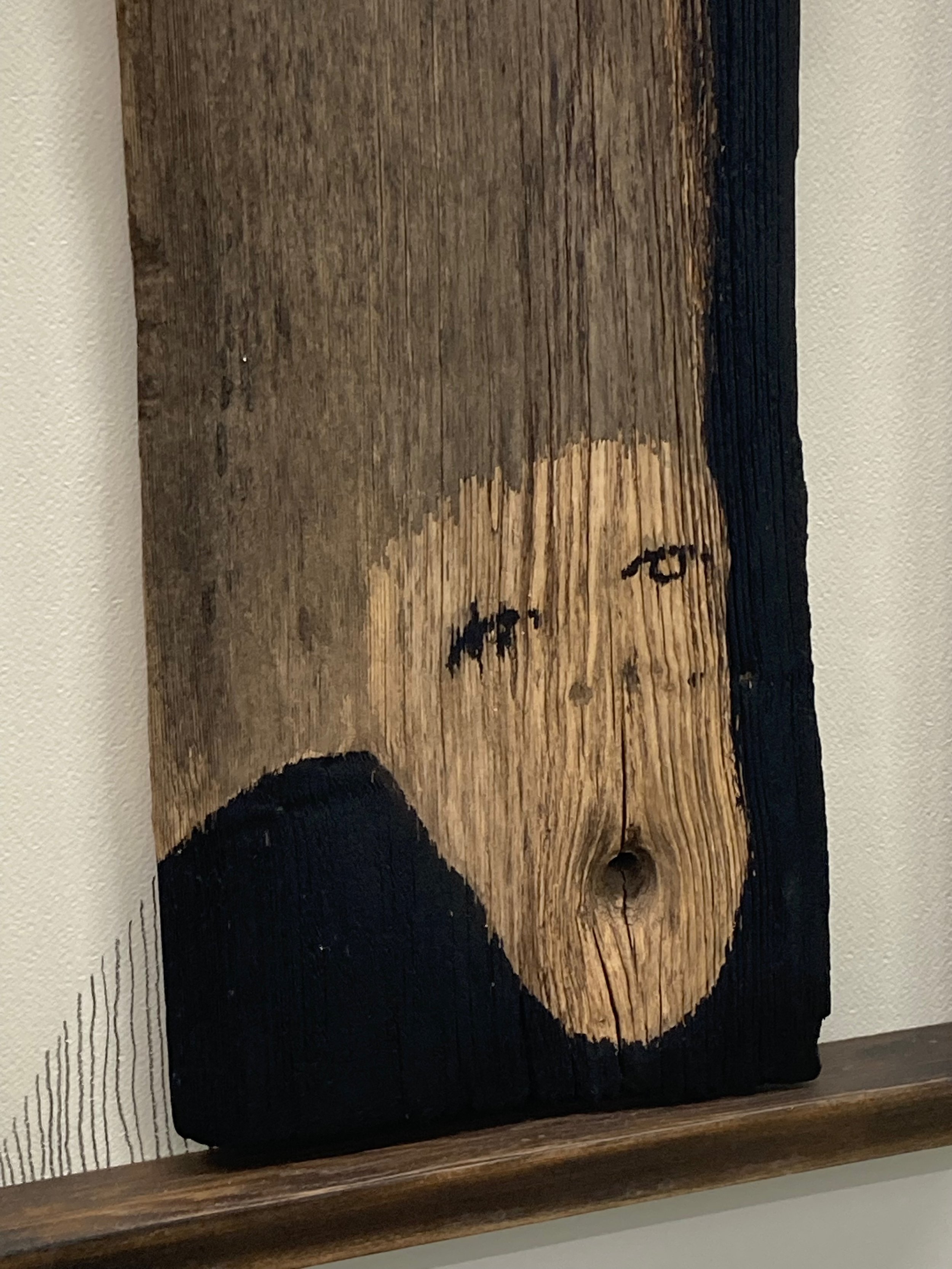

Yun Suknam made her second journey to New York in the 1990s. This time, upon returning to Korea, she started using discarded wood for the first time. It was a combination of a wooden panel work by a South American artist she saw at the Bronx Museum, and a strong impression she got from a persimmon tree at the house of Heo Nanseolheon, a 16th Century Korean woman poet and painter.

Her second exhibition in 1993, Mother’s Eye, also kept to the topic of motherhood, with Yun’s own mother Won Jeung Sook was the protagonist. Won Jeung Sook is said to have never went to school but loved to read, and singlehandedly raised six children after the death of her husband. She was her herself was a condensed figure of the early Korean diaspora, marrying an intellectual who studied in Japan during the Japanese Occupation of Korea and together moving to Manchuria (modern day China) after World War II. The resulting Mother series charted the personal biography of Yun’s mother from Nineteen-Years-Old to For Her Family. The conventional image of a caring, providing mother with a gentle smile is nowhere to be found. In its place are the roughened, crouching figure of a working mother accentuated by the textures of discarded wood, door panels, and washboard. And the use of these everyday objects through scavenging and collecting itself reflects the domestic labor of mothers.

Jane Jin Kaisen

Jin Kaisen was born in Jeju Island, Korea in 1980, and has continuously engaged with the shamanistic traditions of her hometown Jeju even after being adopted and growing up in Copenhagen, Denmark. If artists like Yun Suknam and Seundja Rhee sought creative freedom and a degree of independence from gendered responsibilities of a traditional mother, the latter half of the 20th Century starts to see diasporas experienced at earlier years of life such as adoption or families moving abroad with young children. For children of the diaspora, the tension between a sense of connection to their motherland and the absence of direct lived experience of it provides a line of inquiry into what creates community and belonging. Jin Kaisen even describes this inquiry as a kind of “responsibility” she feels.

“In 2004, I co-founded an artist collective in Scandinavia called UFOlab, or Unidentified Foreign Object Laboratory with four other transnational adoptee women from Denmark and Sweden. It was one of the first collective artist groups of women of color in Scandinavia creating works together. This was also a moment when we were informed by the status of other artists and other social justice activists, scholars, somehow intersecting with Korea — not just transnational adoptees but also diasporic Koreans who began to return.” (Far Near, 2022)

Due to its comparative isolation from mainland Korea, Jeju Island has developed distinct myths and shamanistic rituals. In video works like Community of Parting (2019), these rituals become a way for the artists herself and other diasporic women to connect to their foremothers, with the shaman, typically a middle-aged woman, ventriloquizing them. The video also invokes the Jeju myth of Bari where princess Bari, the very mythical origin of women shamans. Bari is said to have been abandoned by her father, the king, for being born a girl but returns to become the mediator of life and death, and is therefore able to save the very parents who abandoned her. The shaman, then, although a venerated figure in the community with a certain authority regarding rituals, is first and foremost a protector and spokesperson for things forgotten and abandoned. This role makes shamans an interesting entrypoint into coming to terms with the alienation and displacement that accompany diasporas.

Closely related to this interest in inheritance across further generations, Jin Kaisen frequently makes reference to her grandmother who worked as a haenyeo (sea divers in Jeju who are highly trained and often dive without modern equipment).

A more recent work, Halmang (2023), examines another local tradition which is the worship of wind goddess Yongdeung Halmang among a community of elderly women who were, like Jin Kaisen’s own grandmother, haenyeos for most of their lives. Here, halmang is both an affectionate reference to one’s grandmother as well as the name of the wind goddess, suggesting matrilineal connections both between the spiritual and human and between human generations in passing down local histories and traditions. Local histories includes the Jeju Uprising (1948-1949) which was violently quelled by the Korean government and only recently publicly acknowledged - spirituality and ritual become an alternative mode of keeping those painful memories alive. In this video, a long white strip of fabric called sochang visually represents the continuation of collective memories.

Jane Jin Kaisen, Halmang, 2023, Single channel film, 4K. Color / Stereo sound. © Jane Jin Kaisen

Aram Han Sifuentes

Recalling that Seundja Rhee’s move to France set the stage for her sons to also study and and work there, many other younger members of immigrant communities also celebrate their mothers as paving the hard path for adjusting to a new culture. In turn,

For Aram Han Sifuentes, her immigrant experience continues from mother Younghye Han who moved her family to the U.S in 1992, and her own Chicana Coreana daughter. Younghye Han was a professionally trained artist in Korea but chose a life as seamstress upon moving to the U.S, only returning to art after the birth of Han Sifuente’s daughter or Younghye’s granddaughter. From Han Sifuente’s interview with their mother, Younghye Han talks about why she moved to Manteca, California where she worked almost 12 hours a day making a living as a seamstress and dry cleaner:

Younghye Han: “I knew it would be difficult. But I just wanted you and your sister to learn English. Then you both would be able to do anything and get any type of good paying job. I didn’t think about myself so I didn’t know what type of work I would do. I just thought about your future.”

Aram Han Sifuentes, Younghye Han: My Mother's First Exhibition, installation view. Courtesy of Cultural Reproducers

Commemorating the labor and sacrifice that makes possible immigrant families also yields way for solidarity between different immigrant communities. Han Sifuentes centers their practice around communal projects advocating for immigrant rights. They organize workshops creating protest banners and nonggi (Korean folk banners) in Chicago, which as the artist states, are especially powerful for non-citizens who cannot participate in public forms of resistance such as protests.

In addition to the reference to Korean tradition in these banners, sewing and weaving also inherit the gendered and immigrant labor that Han Sifuentes themselves had to learn from the age of six while helping their seamstress mother. For another project based in Chicago, A Mend: A Collection of Scraps from Local Seamstresses and Tailors (2008-ongoing), the artist interviewed tailors and seamstresses who are often sweated laborers working under often unprotected conditions - as their stories start to form a collective history, the fabric scraps she collected from each laborer also formed a net-shaped installation.

Aram Han Sifuentes’ nonggi project, photography by Bun Stout. Courtesy of CanvasRebel

Bibliography

Seundja Rhee

Kim, Maria. “Seund Ja Rhee, Trailblazing Korean Abstract Artist Who Transcended Borders and Boundaries.” SayArt, May 31, 2023. https://sayart.net/news/view/1065620192333458

“Rhee Seundja: Road to the Antipodes.” National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA), Korea, 22 March 2018 – 29 July 2018. https://www.mmca.go.kr/upload/board/201011160000014/2018/03/2018032309425678517239.pdf

“Woman and Earth Period.” Seundja Rhee Foundation. http://seundjarhee.com/works/paint?locale=en

김인혜. “헤어진 세 아들 향한 그리움 작품으로 승화한 화가 이성자.” 조선일보 (Chosun-ilbo), August 7, 2022. https://www.chosun.com/national/weekend/2022/04/23/L645UAGYWJHHXLBPADCFLV5QJE/#:~:text=%E2%80%9C%EB%82%B4%EA%B0%80%20%EB%B6%93%EC%A7%88%EC%9D%84%20%ED%95%9C%20%EB%B2%88,%EC%97%90%EB%84%88%EC%A7%80%EB%A1%9C%20%EB%B3%80%ED%99%98%EC%8B%9C%ED%82%A8%20%EA%B2%83%EC%9D%B4%EB%8B%A4.

Yun Suknam

Catlin, Roger. “Breakthrough Korean Feminist Artist Yun Suknam in Her First U.S. Museum Exhibition.” Smithsonian Magazine, January 30, 2019. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/breakthrough-korean-feminist-artist-yun-suknam-her-first-us-museum-exhibition-180971111/

강보라. “나로소이다: 윤석남 작가 화성 작업실 투어.” 옆짚에 사는 예술가, 2017. http://g-openstudio.co.kr/portfolio_page/ysna/?ckattempt=2

Kim, Hyeonjoo. “Yun Suknam's Arts and the Story of Women.” Yun Suknam. http://yunsuknam.com/zboard/zboard.php?id=text&page=1&sn1=&divpage=1&sn=off&ss=on&sc=on&select_arrange=headnum&desc=asc&no=10

최효민, 한희정. “The Mother of Feminist Art, Suk-Nam Yun.” The Sungkyun Times, August 22, 2016. https://skt.skku.edu/news/articleView.html?idxno=60

Jane Jin Kaisen

Forbes-Carbines, Frances. “What to Do During a Period of Enforced Silence?.” ArtReview, 09 February 2024. https://artreview.com/jane-jin-kaisens-halmang-esea-manchester/

Jin Kaisen, Jane; and Kwon, Lisa. “The Woman, the Orphan, and the Tiger: Jane Jin Kaisen Disentangles Korean History Through Art,” Far Near, May 1, 2022. https://far-near.media/stories/the-woman-the-orphan-and-the-tiger-jane-jin-kaisen-disentangles-korean-history-through-art/

“Jane Jin Kaisen, Community of Parting.” Artsonje Center, July 29 – September 26, 2021. https://artsonje.org/en/exhibition/jane-jin-kaisen-community-of-parting/

Aram Han Sifuentes

“A Mend: A Collection of Scraps from Local Seamstresses and Tailors.” Aram Han Sifuentes. https://www.aramhansifuentes.com/works/a-mend%3A-a-collection-of-scraps-from-local-seamstresses-and-tailors

“Interview: Aram Han Sifuentes.” Cultural ReProducers, November 5, 2016. https://www.culturalreproducers.org/2016/11/interview-aram-han-sifuentes.html

“Interview With My Mother, Younghye Han,” Cultural ReProducers, November 5, 2016. https://www.culturalreproducers.org/2016/11/interview-with-my-mother-younghye-han.html

“Meet Aram Han Sifuentes.” CanvasRebel, January 25, 2024. https://canvasrebel.com/meet-aram-han-sifuentes/