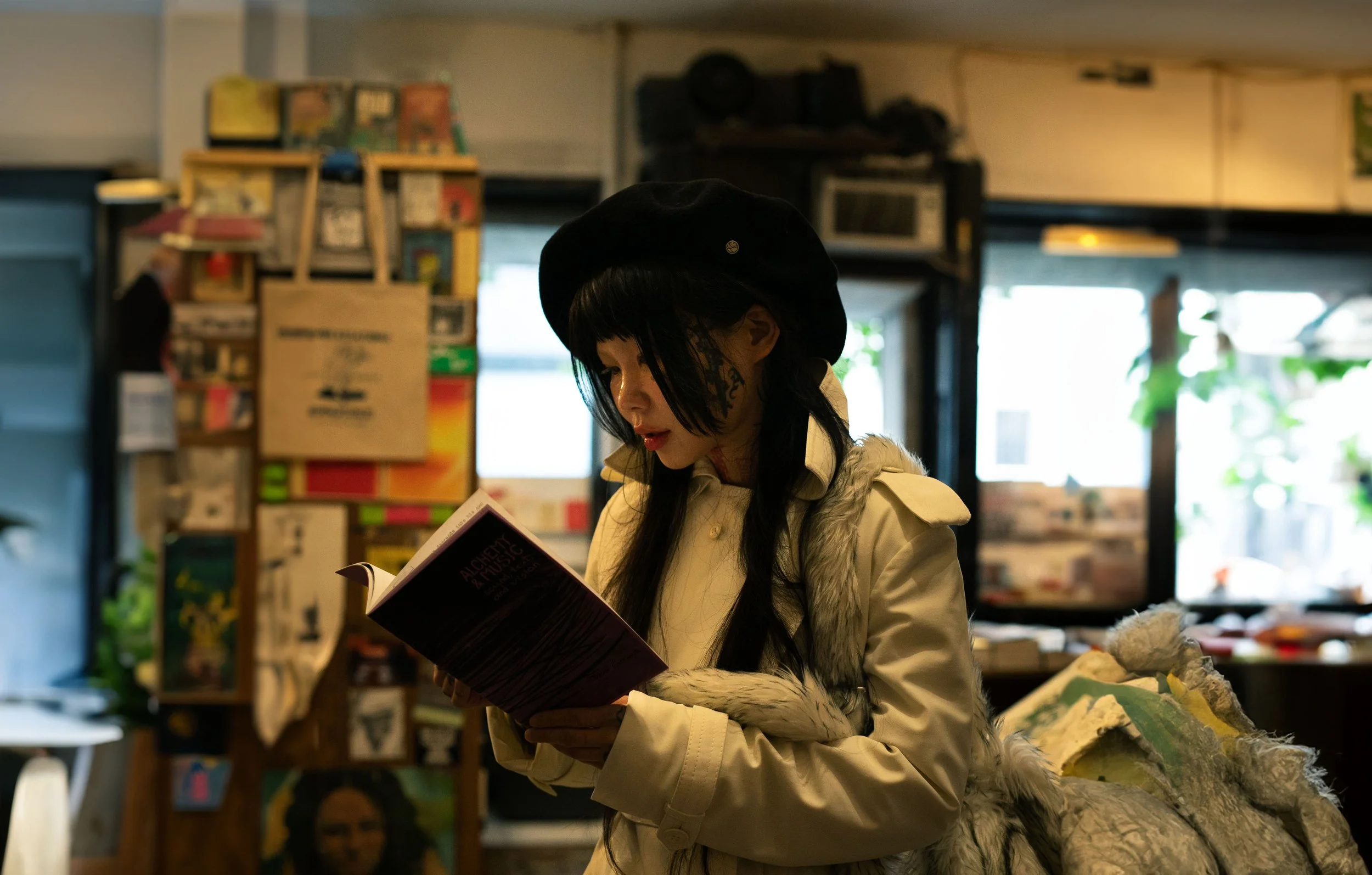

Park Karo

Conjuring Silent Symbols, in Galleries and on Skin

Photo by Sylvie Tamar

Park Karo is a Korean-born artist who creates installation and conceptual art revolving around personal myths, often spoken through the language of science and math. Science and math configure one aspect of her interest in belief systems, which are mediated through perception of self, medicine and knowledge at large, and artists’ role as modern day shamans. Karo considers herself an "immersive artist" whose personal history and experiences become part of the audience's experience. She continues to explore different avenues of interfacing with audiences such as her extensive career as a tattoo artist as well as performance, audience-participatory projects, clothes, jewelry, and perfume.

Karo has participated in group exhibitions at Amado Art Space, Seoul Museum of Art, Alternative Space Loop, Coex Urban Art Break Fair, and Eulji Art Center, all in Seoul. She held solo exhibitions at Subtitled NYC, New York; and Humor Garmgot, Seoul.

We met with Karo on a rainy day in Bushwick, close to Gristle Tattoo where she is guest working until June 8, 2024. Our gratitude goes out to the barista at Swallow Cafe who was patient with our almost hour-long session and camera flashing.

Haena: Let’s start with introductions - please tell us who you are!

Karo: Hello, I'm Karo. The name "Karo" derives from the Spanish name Carlos, symbolizing a free-spirited life like that of a nomad.

From a young age, I immersed myself in art and subcultures. I am the second of four siblings and was raised under deeply religious parents. As I went through a rebellious adolescence, I was drawn to punk culture. I admired how my punk friends addressed social issues through protests and were interested in political philosophy, which made aesthetics and philosophy easily accessible to me. I went on to majored in digital design in high school, learned film photography in college, and specialized in exhibition planning and criticism. Consequently, my work tends to lean towards conceptual and installation art.

Photos by Sylvie Tamar

I enjoy imagining things and translating those imaginations into reality. I see thoughts as pathways—similar to the expansion of neurons in the brain. I named such acts "navigations of thought."

I aim to navigate this vessel, creating fishermen who can catch people, take breaks, have fun, and ultimately become someone who can fully acknowledge and let go of my own death.

H: Wow, I am kind of jealous that you discovered the punk scene in Korea early on. Although I grew up in Seoul, it took me until my mid-twenties to find the right people and places. What advice would you give to people searching for that scene in Korea?

K: Definitely to seek out the venues where action happens! I do think the heyday of underground venues is a bit past since my teenage years, when places like Skunk became centerpoints for the punk scene. It’s funny to see the people from that scene now being married and becoming dads, although some of them are still active and making music. I know a new venue, Baby Doll, recently opened up in Seoul.

H: Speaking of shows, how has your time in New York been so far? Anything new since the last time you visited?

K: I moved to New York last year, in October 2023. Currently, I am traveling around the United States to understand the country's dynamics and potential clientele. Therefore, I am still in a constant state of being a traveler. Although this state of flux may seem challenging, I have a clear mindset that it's okay not to have everything figured out right now.

While feeling like an anxious outsider, I pondered how to express myself through art, which became the basis for my upcoming exhibition (ON-NO) RED at Subtitled NYC (June 1–3, 2024). As part of this exhibition, I am working with a perfumer friend to create scents that complement the exhibition's theme and am also developing background music for the exhibition. This will be my third solo exhibition.

I have started other new projects while in New York, as well. Recently, I produced and sold scarves with graphic designs drawn in a new style. I also purchased fabric from the New York market to make sample clothing, visited sample rooms, and did some sewing.

Left: Park Karo’s exhibition at Subtitled NYC, (On-No) Red | Right: Park Karo’s scarf design. Images courtesy of artist Park Karo.

Visual Art

H: You have already exhibited at major venues in Korea. One of them was at COEX in 2021, where the artist statement mentions that “Belief is also a condition of boundaries.” Contrary to what people imagine when they hear the word “belief,” here you were referring to the belief in scientific, categorized knowledge. At the same time, you use a lot of scientific imagery in your work, especially diagrams. How are you challenging science through the language of science?

K: I consider knowledge to be a type of belief. Knowledge is a systematized promise, which belongs to the category of belief. I believe that belief plays the most significant role in human existence. I want to explain my beliefs to others, but to make explanations easier, I use other beliefs as references, one of them being the imagery of belief inherent in science and mathematics.

In particular, I enjoy creating personal mythical images using the credibility of science and mathematics. I believe that the most important aspect of persuading people is to make what is known easily penetrable.

What is truth? Do facts and falsehoods rely on belief? What do we believe in? The importance we assign to these questions, too, may be a flaw of belief.

Photo by Sylvie Tamar

H: Hypothetically, do you see yourself ever using tools other than science and mathematics to make personal mythical images? Or, have you ever experimented with using other tools?

K: I have thought about making larger-scale installations, made of aluminum, for example. But there are limitations to the medium I can use because of my frequent traveling. Whenever I create installation-based work, it is a huge task to plan where all the material will go after the exhibition closes.

H: The relationship between language and image is another running theme in your works. You often use poetic lines, or fragments of poems. Are there any difficulties in expressing poetic ideas in English for U.S audiences?

K: Yes, indeed. To borrow the words of my dear friend, poet Kim Sono, a single word carries countless meanings and nuances accumulated through the history of the speaker and the society of the same language community. The impact of language is recreated through various experiences and historical events from the individual to the collective and society. For example, my family describes absurd situations as “웃기는 짜장 (funny jjajang; “jjajang” is short for “jjajangmyeon,” Korean adaptation of Chinese black bean noodles).” This phrase originates from the idea that jjajangmyeon must be well-mixed into a messy, tangled state to be eaten, thus likening a chaotic situation to "funny jjajang." This expression would be incomprehensible to anyone outside my family.

I often try to express my thoughts through such metaphors and nuances, but I frequently find it challenging to convey these ideas effectively. This difficulty arises because the process of thinking and understanding differs between cultures, which is also why I quoted Kim Sono earlier.

H: Please tell us about your upcoming exhibition (ON-NO) RED at Subtitled. What should we expect to see? Are you showing any new works, or perhaps old works from a new perspective? What are you most excited to showcase?

K: The exhibition is like a funeral, a mortuary. When I first arrived in New York, everything was unfamiliar. Even though I often travel abroad for guest work, coming here with the intention of moving felt different. My mindset was different from the start. I felt like I was floating midair, having left everything I had built behind and stepping onto a new path. I felt anxious. I found myself asking: “Who am I?” We often mistake ourselves for being “me” even though “I” doesn't really exist.

I decided to paint a self-portrait. I rented a house from my friend at a good price. Since it wasn't my house, I thought I would line the walls with plastic first and paint on canvas on top of it. The self-portrait I started with the intention of painting myself ended up depicting “us” after going through many versions of “me.” It shows everyone walking towards the light, to a place that might be an end or a beginning. I drew myself and “us” with dust-like dots.

After finishing the painting and removing it from the wall, I saw stains left on the plastic from the ink that had seeped through the canvas cloth.

Since these stains are also a residue of the painting, I wondered if this painting was one or two pieces.

It reminded me of the relationship between body and spirit.

We are temporary projections, and the stains are the continuity of that projection.

So, by destroying the original painting, I created my own funeral. I burned the original painting and left only the trace of the original painting (me) projected onto the plastic. I will display these as spaces arranged in frames.

The exhibition title, (ON-NO) RED, comes from the idea that life is when hemoglobin stays in the body, and death is when that hemoglobin disappears.

This installation will be accompanied by drawings, video works, text, ceramic sculptures, and music. So everything will be new work.

Idea development for (ON-NO) RED (Subtitled NYC, 2024). Images courtesy of artist Park Karo.

H: During your early career (2014), you created multiple performances or audience performances through instructions. Is this a type of work you see doing again in the future? Or were there any major changes in your creative direction?

K: In my early work, I focused on more intangible projects. I translated my concepts into performances, encouraging audience participation. I believed performance art was the most avant-garde and unownable form of art. Since art ultimately becomes someone's possession and a commodity traded in the market, I had a strong aversion to this market dynamic in the beginning. Instead, I found joy in creating art that remained free from ownership and existed as a happening.

However, as I thought more about persuading people and conveying my intentions, my work shifted towards more tangible forms. In truth, the medium and form of my work are not crucial. I use whatever medium is appropriate for my thoughts at the time.

Being on the Move

H: Please tell us more about the concept of “small boundaries (작은 경계)” that you mention in your statement for solo exhibition Boundary Between A and B at Gallery Villa Hamilton (Seoul, 2020).

K: When I talk about boundaries, I'm referring to the points of friction that form differently for each person due to their environment and sense of self. In that context, "small boundaries" would represent those small points of divergence caused by such factors. The realm of boundaries is vast and not simply about opposites. It's about how I perceive and create various boundaries that I find important. I think it's a part of cognitive ability.

H: I wonder if your frequent traveling influences your interest in boundaries at all. When did you decide to shift from working in Korea to the U.S? What motivated your decision?

K: It probably does. Traveling has made me feel like a foreigner often. The tattoo shop I currently work at in Brooklyn, Gristle Tattoo shop, was my first shop to host me. The owner, Dina, impressed me so much that I never guested at any other shop. Dina is a friend who is also a doctor, involved in animal rescue activism, and runs a vegan cheese business. She suggested that I come to the U.S. and helped me with the visa process. That’s when I started preparing to move here permanently.

H: I often feel that there are words, feelings, and sentiments that are hard to translate from one language to another. Is there any word or concept central to your practice that you find difficult to convey in a language that is not Korean?

K: I am captivated by symbols that transcend language. For instance, my work titled Contemplating Tail explores this idea. It dreams of telepathy, of unspoken minds.

I reflect on the world of language that silent symbols convey.

While language can produce sound, symbols remain silent, conveying only marked images. I perceive this as the magic and mystery of symbols. We must consider what we perceive in the realm of images, the spiritual, representation, and materiality.

Photo by Sylvie Tamar

H: Identity has become so much more complicated because information and cultural content is shared so quickly across the globe. Do you think about experiences specific to Korea when you make art? What is your relationship with the shifting definitions of “Korean-ness”?

K: I don’t think I’ve ever specifically considered elements unique to Korea in my work. As someone who has had many tattoos from a young age, I’ve faced discrimination early on, but this wasn’t unique to Korea—it was the same in Europe and the U.S. Beyond tattoos, I often face discrimination for being “Asian” and “female,” which are even more defining categories for me. My identity as an Asian woman has more significance to me than my national identity.

Tattoos and Artist-as-shaman

H: Of course, many people also know you as a tattoo artist with a signature style that really stands out. How did you start tattooing?

K: I started tattooing through an arts school club gathering. At the suggestion of a friend, I took up tattooing, and that friend became my mentor as I began my journey into tattoo art. Although I had been interested in tattoos since receiving my first one at 16, I never imagined becoming a tattoo artist. It's amusing how this work now sustains and supports me. It goes to show that opportunities and paths often come from unexpected places.

Photo by Sylvie Tamar

H: There seems to be a mutual relationship between the visual art you make and your tattoos. I saw that one of your clients got a tattoo of the Egoer installation, for example. How does your tattooing experience affect your perception of the relationship between art and audiences?

K: I’ve thought a lot about how to describe myself and my work, and I’ve settled on the term "immersive artist." My personal history and experiences become part of the audience's experience. I present fragments of my own experiences to the audience on a one-to-one basis. For instance, in my first solo exhibition in 2020, The Boundary of A and B, only one person could view the exhibition at a time. This was designed to make individuals reflect on their own boundaries and how they confront them, as a study of how 1:1 sensory experiences work without the presence of others. During the COVID-19 pandemic, I experienced living in isolation at a hospital that came to be known as “Mapo 15”, which this exhibition explored. It was also featured in the Korean TV documentary, EBS Post-Corona Part 2.

H: I have experienced very different perceptions of tattoos in Korea and here in the U.S, especially in Brooklyn where it’s harder to find someone without one! Any funny stories arising from these different attitudes?

K: Well, having spent a significant amount of time in the Hongdae area** in Korea, I haven't noticed major differences yet—especially since Hongdae is also a place where diverse subcultures thrive, similar to Brooklyn. There's even a joke that says "Hongdae is now only left with rappers and tattoo artists," highlighting its reputation as a hub for cultural exchange.

**Hongdae is a neighborhood in Seoul, named after Hongik University that the area grew around. Supported by Hongik University’s Fine Arts program and cheap rent that allowed for the influx of young artists, it became the center point for Korea’s indie music scene in the 1990s, followed by clubs, cafes, and other underground cultures like the punk scene that Karo mentions.

H: Your (Un)certain diagnosis (2019) made me think about how tattoos are both medical and shamanistic - they are classified as a “medical procedure” in Korea after all! Why is this ambiguity important in tattoos functioning as talismans?

It's not so much the ambiguity that is important, but rather the idea that artists in the modern era function similarly to shamans.

Photo by Sylvie Tamar

K: My work in 2019 was a development of an earlier piece from 2013, which also explored the trust established by hospitals. I saw hospitals as holding a kind of belief system similar to that of shamanistic shrines. Through research, I discovered that hospitals originated from ancient Greek temples, which then became hospices and eventually modern hospitals. I've always studied belief systems, and talismans are one aspect of this. I wanted to create a structure where belief operates within space, like at a hospital (or shrine), analogous to how talismans work.

H: That’s really great. Seems like that one-to-one relationship works between you and the audiences, as well as between the audience and themselves reflexibly. Lastly, I’ve been seeing a lot of artists trying to get into tattooing, or tattoo artists trying to get into exhibiting visual art. As someone who has been doing both, what advice do you you have?

K: I do think that for me, tattooing and creating visual art take completely different approaches. I see tattoos as being completely commercial, whereas a lot of my other art is conceptual. Oftentimes, I think artists become too tied to their signature style, or conceptual direction, in tattoo design, and unfortunately that means fewer clients will seek you out. I became more comfortable through time with adapting to clients’ requests. I’ve tattooed puppies’ faces or flowers, for example.

For general advice for artists getting into new areas, it would be to reflect on whether you have a compelling reason for getting into a new discipline — or if maybe you are doing it because it looks “cool”! I say this because for me, making art is a drive and a responsibility that I feel I have no choice in.

Another thing is self-discipline. What I love is creating work. However, to create work, I need to establish definite deadlines—otherwise, it can endlessly prolong. Therefore, I make a great effort to produce a lot of work.

Interview and editing by Haena Chu / Original text and artwork images by Park Karo / Photos by Sylvie Tamar

All photo credit marked in captions